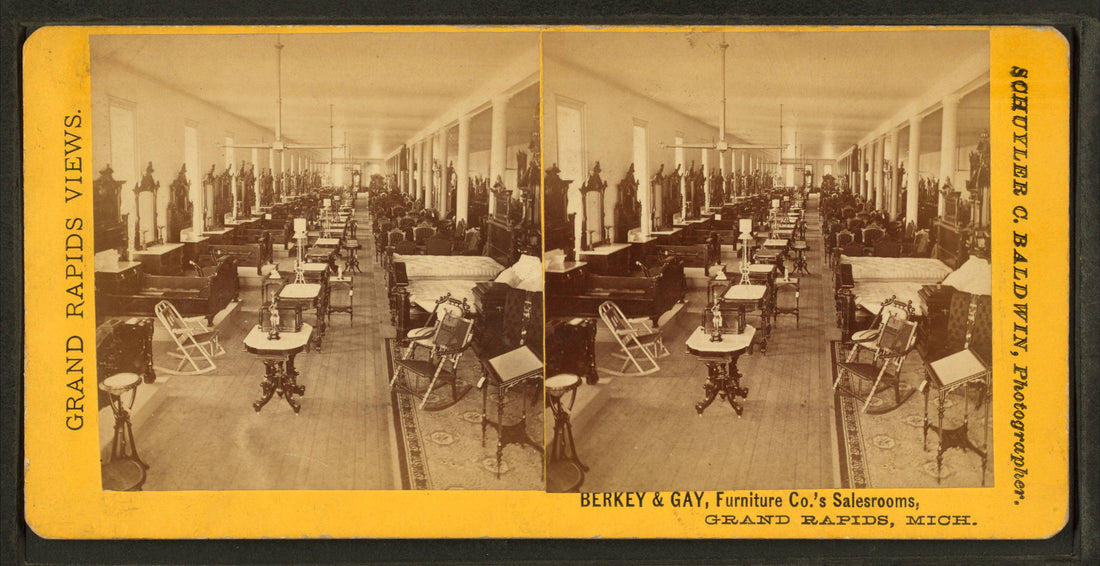

In the mid-nineteenth century, homes in America were dressing up. Parlor rooms and chamber suits became a Tetris of needlepoint seats, tea carts, rocking chairs, and lush fabrics. Pomp outweighed necessity. Furniture gushed with personality, celebrating specialization, ornamentation, and decoration. Regality was not reserved for the wealthy class. As Ken Ames says in Grand Rapids Furniture: The Story of America’s Furniture City, “The furniture industry flourished because people deeply believed in furniture. They believed that it expressed important truths about them as individuals, about their personality and character, about the quality of their lives, and about the level and nature of their civilization. To most people who shared the values of mainstream Victorian culture, living the good life meant living with good furniture.”

Postcard of the Phoenix Furniture Company factory and lumber yard in Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1909.

Berkey and Gay Furniture Company, Rubbing Department, 1929.

“The Furniture City”

The furniture industry of Michigan made its debut at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, the first World Fair hosted by the United States. Grand Rapids-based furniture companies such as Berkey & Gay, Nelson, Matter & Company, and Phoenix Furniture Company led the way for innovative and fast-paced design, proving that a mechanized process of manufacturing had developed beyond the traditional, handmade approach. Subsequently, towns across Michigan erected dozens of factories replete with mechanized technology. The state reached its golden years in mass-producing signature cabinets, tables, couches, and other pieces for the home. No other city producing furniture in the United States could outpace the production taking place in Grand Rapids. The city quickly garnered its title, “The Furniture City.” Manufacturing overflowed into the city of Holland and later, into Zeeland. These cities centered around furniture manufacturing, employing nearly half of its population with jobs that touched every part of the process.

But why Michigan? And more specifically, why Grand Rapids? For one, 95% of Michigan housed untouched forests, and Grand Rapids itself sat directly adjacent to wood such as pine, walnut, and oak. The state also had sufficient labor, optimistic investors, quality craftsmanship, and an appreciation for technology. Individuals moving West, namely immigrants from Poland, Germany, and the Netherlands, fell in love with the land and dropped their packs. Michigan’s infrastructure flourished with the development of railroads, bridges, canals, and roads that served the most efficient routes to and from the factories, which sat next to the Grand River and its reliable supply of power, water, and transportation.

Turning the Page

By the early twentieth century, Grand Rapids experienced a new chapter in its evolution, one that involved dwindling forests, aging factories facing costly repairs, and competition for labor, all of which led the city to take a backseat in its title and reputation. Additionally, by the 1930s, the arrival of the Great Depression muted the value placed on stylish living, and people’s needs reoriented around comfort, low cost, and simplicity. From 1945 onwards, a majority of residential furniture manufacturing moved away from Michigan, reestablishing itself in North Carolina and other Southern factories. But not all was lost. By the end of WWII, Christian G. Carron, former head of the curatorial department of The Public Museum of Grand Rapids, notes that furniture companies in Grand Rapids “nearly doubled, from 47 in 1940 to 88 in 1947…[becoming] clear that the pent-up need to buy furniture after 15 years of depression and war, combined with the increased number of marriages and new homes under construction, meant prosperity for furniture makers.” However, post-war recovery in Grand Rapids was slower due to the fact that families did not have the same kind of spending capital they once had. Furniture was a luxury, especially at the kind of caliber produced by furniture makers in Grand Rapids.

Change was edging closer. Factories were closing. Others were being bought out by larger players. Residential furniture was no longer prized, as it once was. The good news? Post-war America was in a state of rebuilding and all of those buildings needed furniture. The same talent that once took on residential manufacturing pivoted, applying their craftsmanship in woodworking and upholstering to meet the durability and ergonomics required of commercial furniture manufacturing that supplied places like schools, offices, and large auditoriums. Companies such as Herman Miller, Haworth, and Steelcase championed commercial furniture designed for efficiency and mass production.

Charles and Ray Eames in their home, Los Angeles, California, 1958

In this novel landscape, furniture manufacturing in Michigan found its footing due to the leadership of Herman Miller’s founder, D.J. DePree. Although DePree himself was rather austere and conservative, he remained open to outside influence. After DePree bought Star Furniture Company, he teamed up with New York-based designer, Gilbert Rohde. Their partnership paved the way for innovative design that would define the twentieth century. By 1945, designers at Herman Miller, including George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, and Isamu Noguchi, shifted away from traditional, ornate furniture. Instead, they leaned into a more modern and experimental aesthetic: bright colors, odd shapes, and varying weights that could produce something equally beautiful using half the amount of material.

The movement of the 1950s and 1960s ushered in what’s now known as mid-century modern design. Notable designs of the era included the Eames Fiberglass Armchair, Robert Propst’s “Action Office” cubicle, and Nelson’s bubble lamps. Floyd’s Head of Product, Tony Rotman, says, “From my viewpoint, mid-century design was a response to a cultural shift in society. Those designers were producing furniture for the masses that was so inexpensive, high quality, and very functional to the shifts in how people were living.” The highly regarded Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan served as a breeding ground for some of the most influential mid-century designers and their iconic work. Although mid-century designs phased out during the latter half of the 1960s, popularity surged once again in the 1980s and 1990s, prompting reissues of signature pieces and satisfying the demand for a direct to consumer model.

Eames Fiberglass Arm Chair

Floyd gets its start in Detroit.

Floyd co-founders Alex O’Dell and Kyle Hoff first met in Detroit at North Corktown’s Practice Space. It’s there where the idea for Floyd first began to grow its legs. Both from the midwest themselves (Michigan and Ohio respectively), O'Dell and Hoff were proud to be tapped in to the rich legacy of midwest manufacturing and ingenuity. “As we began to build the business, we found that our location in Detroit not only gave us great access to the manufacturing infrastructure of the Great Lakes Region, but we were also in a state with a rich history of furniture production." Hoff says.

Floyd HQ, Eastern Market, Detroit.

Today, Floyd’s manufacturing footprint mainly runs from Pennsylvania to North Carolina, and Tennessee, with around 25-30% of its products being manufactured by partners in West Michigan. Many of Floyd’s suppliers are multigenerational businesses: industry veterans who pride themselves on true craftsmanship, institutional knowledge, and respect for the design iteration process. “Being in Western Michigan, the whole entire supply chain is right here at our fingertips, within a 30 mile radius,” says Todd Folkert, CEO of Bold Furniture, one of Floyd’s Muskegon-based manufacturing partners. “A number of our employees, their fathers worked for Steelcase.” For these individuals, Folkert adds that the intrigue lies in being able to both influence and shape work environments and larger design trends for corporate America. The longevity in career makes sense in the context of nineteenth-century Grand Rapids furniture makers, whose typical trajectory required patience and dedication, putting in years of apprenticeship before moving up the ladder to a journeyman and then an expert.

Akin to Folkert’s employees, Floyd’s very own Tony Rotman grew up in West Michigan, where his dad worked at Herman Miller for 40 years. Rotman speaks to the pride and resiliency of manufacturing companies in the area. “The working mentality of West Michigan is culture, community, and resourcefulness. It’s working hard, not wasting anything, and smart thinking.” Rotman returned to Michigan after working on IKEA’s product development team in Sweden. Similar to how mid-century modern designers were responding to a cultural shift in society, Rotman says, “What excites me most about Floyd is that we’re pushing into the 21st century with an obvious nod and love for those who came before us, but focusing on the problems that we face today: climate change, chemicals and materials, human and environmental health. One of our design principles is [asking the question] ‘Why does this deserve to exist?’”

1. Berkey & Gay Furniture Co.’s salesrooms, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Schuyler Colfax Baldwin, New York Public Library; 2.. Postcard manufactured by Will P Canaan Company, Grand Rapids Public Museum; 3. Grand Rapids Public Museum; 4, 5, & 6 Grand Rapids Public Museum; 7. Julius Shulman, photographer, 1958, for Time Magazine, The Getty Research Institute Special Collections; 8. Photograph by Rama, Wikimedia Commons, Cc-by-sa-2.0-fr.

This will be hidden in site