Enzo Mari: Remembering a Design Revolutionary

The Italian iconoclast passed away last week.

Kate Connors

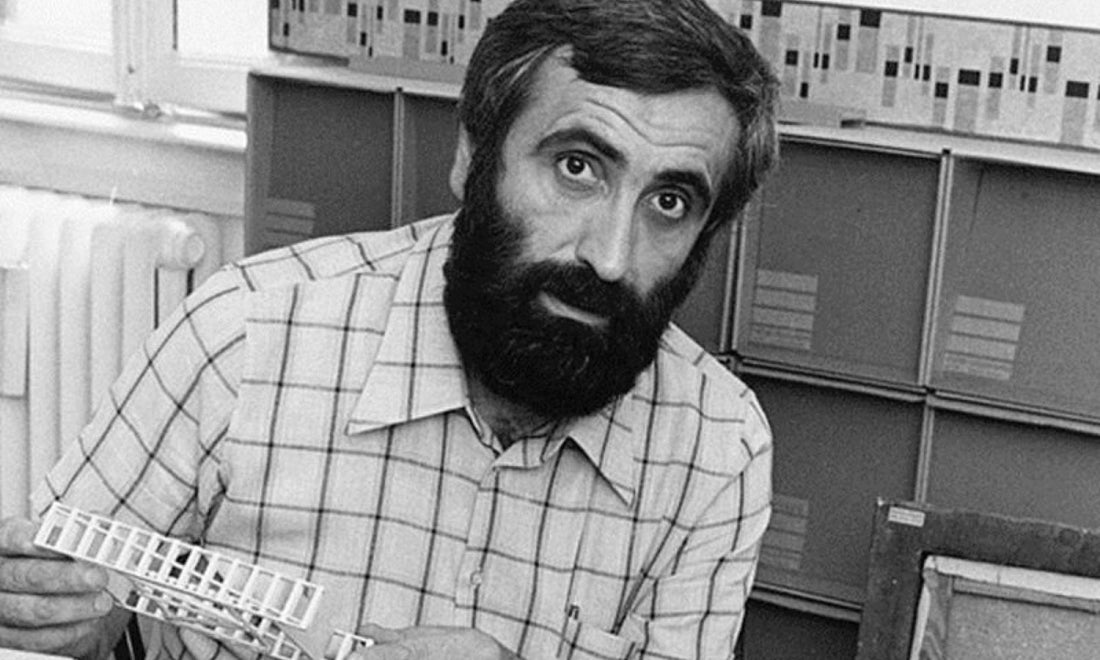

1. Header image: Enzo Mari in his workshop, with models from Autoprogettazione. / 2. The 16 Animals Puzzle, cut from a single sheet of wood. / 3. Mari's studio in Milan. / 4. Mari, later in life.

What qualifies as design? Does it require sleek lines and luxurious materials?

Enzo Mari once proclaimed “design is dead.” For the revolutionary Italian industrial designer, perhaps a hyper-rarified version of design deserved the fate. But in its place, Mari envisioned a physical world shaped collectively, a democratic expression of form and function accessible to all.

For Mari, design was political and personal. After his death last week, it only seemed fitting to examine the life of the iconoclastic figure.

Early Life

Enzo Mari began his life in Northern Italy, born the son of a local artisan in 1932. He skipped high school and college, working as a street peddler through the second world war. It wasn’t until 1952 that he enrolled at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts to study sculpture, painting, and stage design.

His early designs betrayed an interest in simplicity of construction — particularly notable is his 1957 16 Animals Puzzle, which used a single cut to fashion 16 interlocking animals from a single wooden board.

A children’s puzzle might not sound overtly political, but the piece demonstrates what would become Mari’s guiding approach: designing objects that centered the pleasure and ease of the worker producing them.

It was a priority born from Mari’s Marxist ideology, a radical reinterpretation of design that had always been consumer-focused. But Mari’s political convictions extended further into his work. He believed in designing for affordability using low-cost materials, and took a pragmatic approach rooted in his ethics — meaning that many of his designs lacked the “aggressively promotional” nature of consumer-centered products.

Autoprogettazione?

A notable example of Mari’s egalitarian approach to his work comes in his 1974 book Autoprogettazione?.

In the introduction, Mari’s title is defined — “It is not easy to translate into English the Italian word autoprogettazione. Literally it means auto (self) and progettazione (design). But the term self-design is misleading since the word 'design' to the general public now signifies a series of superficially decorative objects. By the word autoprogettazione Mari means an exercise to be carried out individually to improve one's personal understanding of the sincerity behind the project.”

Autoprogettazione? is an instruction manual, the blueprints for a series of simple wooden furniture objects that can be constructed by the reader. It calls for only the simplest of materials: commonly available lumber and nails. There is no joinery or ornamentation in Autoprogettazione?.

The book was in pointed opposition to the exclusivity and what Mari deemed the ‘laziness’ of his design contemporaries. Most importantly, Mari distributed the book for free (long before the advent of PDFs made such an endeavour easy), subverting the capitalist notions of ownership that he so despised. Although the book would go on to be formally published, he later donated the rights to reproduce the furniture in the book to a German charity, CUCULA, which supports African refugees.

That’s not to say Mari was entirely self-serious. While he was known for his cranky attitude and cigar habit, his work often exhibited a playful vision of modernism. Geese, elephants, lions and pigs were common elements of his graphic designs.

He designed imaginative toys, and his illustrations can be found in several Italian children’s books. His work is characteristically simple, but it takes a bold approach to color and line that is appealing to young and old alike.

The Enzo Mari Philosphy of Simplicity and User-Focused Design

Enzo Mari pioneered a philosophy of design that paired simplicity of material with consideration for both the builder and the user. And while he may have declared design as dead, perhaps he spoke with some irony.

Because his work, and the ethics which formed his guiding principles have served to inspire the work of designers ever since.