Everyone knows what it’s like to search for a missing puzzle piece. The artist Sol LeWitt was counting on that when he created Incomplete Open Cubes in 1974.

LeWitt sketched out 122 different ways of “not making a cube,” a series of lines that feel like a mathematician got interrupted in the middle of solving an equation. He left it up to us to finish the cube. We have to try and understand how everything fits together.

LeWitt’s Incomplete Cubes helped frame the concept behind the Floyd Sectional. We saw how a simple geometric shape could be so much more with the addition of imagination.

The Vision of the Artist

At Floyd, we’re drawn to artists willing to challenge the convention of their time. LeWitt has been characterized as “a founding father of both minimalism and conceptual art.” He upended the art world in the 1960s by suggesting that physical works had no value, but instead, that art was the vision of the artist.

We don’t accept that things have to be a certain way. But instead, look for what is possible when you strip away convention. We intentionally made The Sectional to adapt to different times and spaces in your life. We wanted a piece that spoke to the world of your imagination. The world, as seen, by Sol LeWitt.

"For each work of art that becomes physical there are many variations that do not."

An Artist and Thought Leader in Minimalism and Conceptual Art

LeWitt is a standout figure claimed by two major art camps. Minimalists appreciate his clean lines and use of the simple shapes we are all taught in kindergarten. Conceptual artists will point to his stance that the final piece is not the work of art.

Art, according to LeWitt, was found in the process of creation.

LeWitt was born in 1928 in Hartford, Connecticut, to Russian Jewish immigrants. He was classically trained as an artist, graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Syracuse University.

After serving in the Korean War, he moved to New York City in 1953. He developed an appreciation for visual layouts while working at Seventeen magazine. And it’s not hard to see how a year as a graphic designer in the office of architect I.M. Pei translated to a worldview that drawings were as important as the actual execution of those drawings.

But his most formative position was as a clerk at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960. He worked alongside future stars of the Minimalist movement, Robert Mangold and Robert Ryman, among them.

He was also immersed in the emerging poles of pop art and abstract expressionism captured in the groundbreaking exhibit, “Sixteen Americans,” that showcased the work of Jasper Johns and Frank Stella.

"Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely

and logically."

Breaking Away from Pop Art

LeWitt rose to fame in the 1960s as he pushed back on the popularity of pop art. His “structures,” what he called sculptures, began with a series of closed-in boxes. He soon stripped away the walls and exhibited chunky, bold outlines of cubes.

Those early structures had weight and form that counterbalanced the spontaneous brushstrokes of painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, abstract expressionists who rose to prominence in the 1940s and 1950s.

LeWitt didn’t seek to draw attention to himself, but his work greatly influenced his contemporaries. The painter Chuck Close began experimenting with the grid method for photorealistic portraits because of LeWitt’s process. And the renowned minimalist sculptor Eva Hesse relied on his advice and support throughout her career.

A Letter to Really Listen To

“You belong in the most secret part of you,” LeWitt wrote in a letter to Hesse. “Don’t worry about cool, make your own uncool. Make your own, your own world.”

He encouraged her and other artists to find the empty space within, the space they feared. Because he believed it was there that they would find something to say.

It’s rare that artists get to coin the name of a movement. But Sol LeWitt did just that in 1967 with his essay, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art.”

“The idea itself, even if it is not made visual, is as much of a work of art as the finished product,” LeWitt wrote.

A Comment on Art

A second piece, “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” published two years later, further laid out the case for concepts having artistic merit. The final of 35 sentences cheekily insisted that the essay itself was a “comment on art, but not art.”

"Successful art changes our understanding of the conventions by altering our perceptions."

Bold, Dimensional and Bright Wall Installations

LeWitt is best known for his wall drawings: vast installations, wherein he provided detailed instructions for other artists to follow. The drawings were modular, meaning they could be rebuilt in other spaces or years later so long as LeWitt’s blueprints were followed.

The first of these, Wall Drawing #16, was exhibited at the Paula Cooper Gallery in 1969. LeWitt envisioned a series of grey bands, 12 inches wide, that would intersect horizontally, vertically, and diagonally.

After the installation, LeWitt was struck by how imperfections in the wall and a heavier hand lent different qualities of light and dark to the piece. The small differences in pencil lines that drew his eye were “beyond the scope of planning, they are inherent in the method.”

LeWitt created a dialogue by providing other painters with instructions. Their interpretation of what he wrote and how they chose to wield their brush is not only visually interesting, it invites viewers to think about where art begins or ends.

Inspired by the colorful frescoes he saw during a decade of living in Italy in the 1980s, he brought daring pops of color to sterile white spaces in the latter half of his career. His pieces called attention to the space where they were placed. His drawings defined and anchored walls. They encourage us to fill in the gaps and make connections.

The wall drawings were often destroyed at the end of an exhibition, a bang of the hammer that the pieces were ephemeral. Often only LeWitt’s written instructions remained of the more than 1,200 pieces he ideated over four decades.

Warm Minimalism

LeWitt’s work presents a puzzle you will feel compelled to solve. His orderly, linear drawings were often minimal; but never cold.

In many ways, they mirrored the artist. LeWitt was a reserved man with a wry sense of humor. When asked about the significance of his wall drawings, he noted, “I think the caveman came first.”

Art That Endures

Although he died in 2007, Lewitt’s wall drawings are still produced and exhibited posthumously. Sol Lewitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective, a collection of 105 pieces that spans over four decades and 27,000 feet, was installed at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in 2008 and is slated to run through 2043.

Yet, LeWitt would not have seen this as his own legacy. It was, instead, his willingness to expand the definition of art that endures.

He placed concepts alongside finished works. He taught generations of artists to value their ideas. He built a foundation for our imaginations and, in doing so, showed us what’s possible when you’re willing to challenge the status quo.

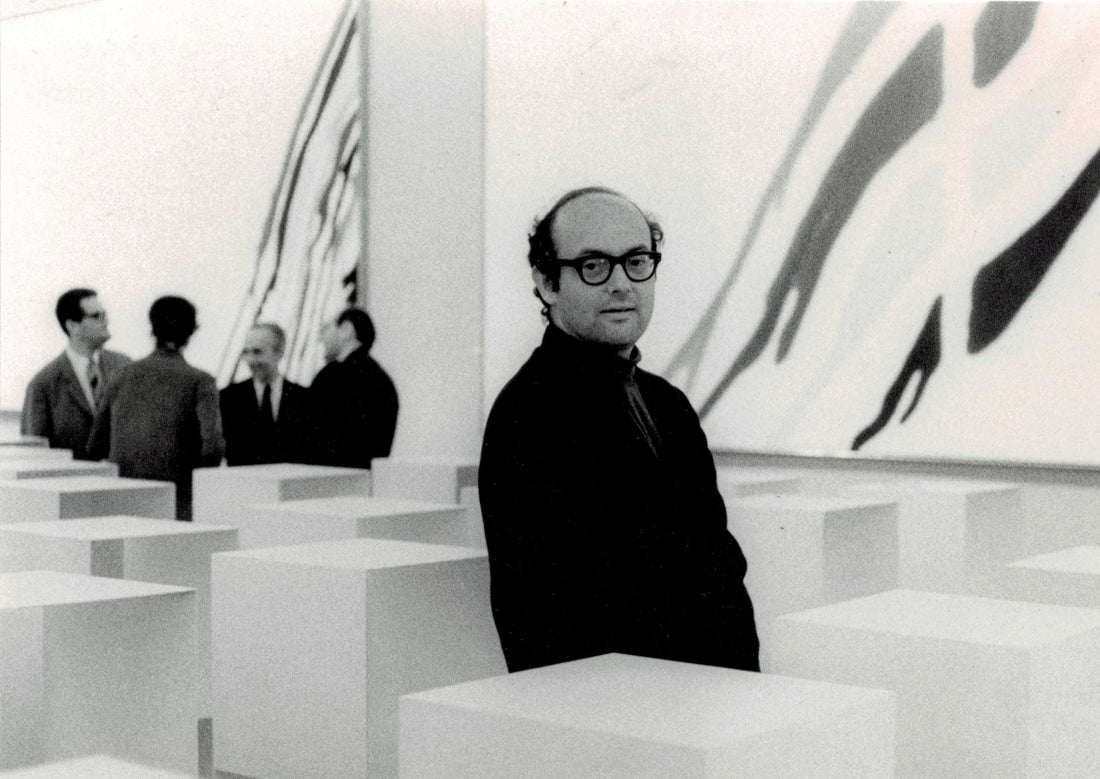

1. Sol LeWitt at Documenta with his work Seriality. Photo by Maria Netter Basel, © The LeWitt Estate / 2. Untangling the puzzle of Sol LeWitt’s open cubes - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art / 3. Nine-part Modular Cube, 1977 - Art Institute Chicago, © 2008 The Estate of Sol LeWitt / 4. Sentences on Conceptual Art, 1968 - The Museum of Modern Art, © 2021 Sol LeWitt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / 5. Lines from the Ends of Lines, from the portfolio, The Location of Lines, 1975, etching on paper - Smithsonian American Art Museum, © 1975, Sol Lewitt (Top Left) / 6. Color Bands, 2000, linocut on paper - Smithsonian American Art Museum, © 2000, The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (Botton Left) / 7. Wall Structure, 1963 - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, © The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (Right)

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art:

8. Wall Drawing #439 / 9. Wall Drawing #579 / 10. Wall Drawing #1171 / 11. Wall Drawing #1042

This will be hidden in site